Meet Your SoulMate Today

My Soulmate Finder

The film Oppenheimer is approaching a worldwide gross of $1 billion, making it the highest-grossing biographical film on record. It’s a tragic irony that the scientific genius in whose shadow Oppenheimer stands is a woman who has been erased from history—a Jewish physicist whose breakthrough discovery made Oppenheimer’s work in the Manhattan Project possible. I discovered her—or, more accurately, she discovered me, twenty years ago in the microfiche room at the New York Public Library.

In the August 6, 1945 edition, under the blaring headline: FIRST ATOMIC BOMB DROPPED ON JAPAN; TRUMAN WARNS FOE OF A ‘RAIN OF RUIN,’” the New York Times traced the simultaneously terrifying and wondrous development of the atomic bomb, its scientific history, and the race between the Allies and the Germans to build it and use it first.

Somewhere below the fold, buried in a long paragraph, this sentence appeared, as if highlighted in neon: “The key component that allowed the Allies to develop the bomb was brought to the Allies by a female, ‘non-Aryan’ physicist.”

I scanned the next paragraph looking for the name of this “non-Aryan” woman. No name. No photo. Nothing.

A female Jewish physicist was responsible for the single most important scientific discovery of the twentieth century. Her work has, literally, changed the world. Why isn’t her face staring out of every science textbook?

I felt this woman reaching her hands out to me from the microfiche screen, placing them firmly on my shoulders and shaking me, hard. Her words were muffled, but impossible not to hear and understand:

Why can’t you see me? Why don’t you know who I am?

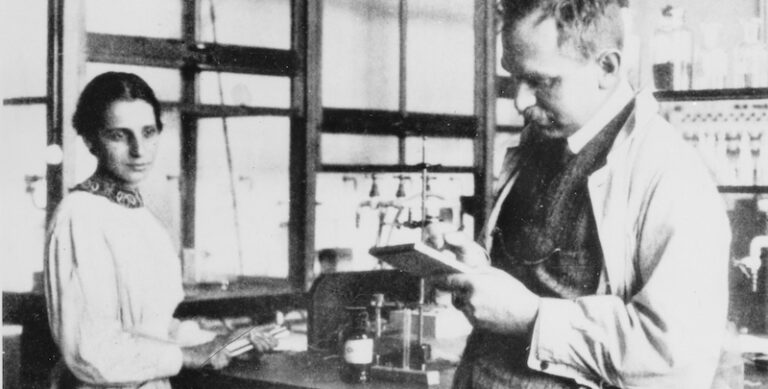

You’ve seen all those photographs: teams of men, all in suits, vests and ties, hair slicked back, every one of them smiling for the camera, smiles that conceal a boyish pride. Boys who grew up with their Chemical Magic sets, showing off their tricks and crowing, “Look! Look what I made!” There they all are, in photograph after photograph, on the steps of the university library, in their laboratories, the proud young men of science. I, too, am there. You must look closely to find me—my thin frame hidden by over-eager young men, crowding into the frame, craving the attention and the spotlight. But I’m there. And I, too, have a story.

Someone must tell my story. You! You must tell my story!

It took 20 years of research, writing, revising, and editing to keep my promise to the mystery woman. My book, Hannah’s War, published by Little, Brown in 2020 was inspired by the story of Dr. Lise Meitner. An Austrian Jew, she was working at the highest levels of research at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin, the premiere scientific research institute in the world, in the 1930s. I tore through her diaries and letters and discovered that her primary focus, along with that of her long-term partner, Otto Hahn, was radioactivity and nuclear physics.

Meitner and Hahn were on the verge of splitting the atom when Germany annexed Austria in 1938. Meitner’s privileged position, and all the protections her colleagues had promised, evaporated within six terrifying hours, as she fled Berlin, just minutes before she would have been captured and sent to the camps. A once-trusted colleague had, in fact, been the one to notify the S.S. of her location.

Otto Hahn, who remained in Berlin, was so dependent on Meitner that he continued to collaborate with her, even after she’d fled to Sweden. He sent her the results of their experiments on postcards via courier. It was Meitner, not Hahn, who analyzed the results and discovered that they had split the atom. It was Meitner, not Hahn, who coined the term for her discovery—“nuclear fission”. It was Hahn, however, who published the paper in “Die Naturwissenshaften” without Meitner’s name on it, falsely claiming that the discovery was based solely on insights gleaned from his own chemical purification work, and that any insight contributed by Meitner played an insignificant role.

In his paper, Hahn had trouble explaining his own findings; ironically, it was Meitner, in a follow-up letter to the editor, who explained the mechanisms behind “Hahn’s discovery.”

After the war, when Hahn was awarded the 1945 Nobel Prize for the discovery of nuclear fission, he conveniently left the record uncorrected, robbing Meitner of the Nobel Prize she rightfully deserved. In Meitner’s diaries, she writes about sitting in the audience at the Nobel ceremony, hoping that Hahn would mention her name, which he did not.

The purpose of science is to investigate, discover, and explain the truth about the natural world; the Nobel Committee, however, seems more devoted to perpetuating sexist lies than to correcting the record.Her disappointment was palpable, but it was accompanied by a kind of resignation I understood all too well, the resignation every woman feels when they’ve raised their hand with a great idea, only to be ignored and then to have a man repeat their idea (often word-for-word) be lauded for his brilliance and given the credit. In her diary, Meitner also conveyed a familiar self-deprecating justification of Hahn’s omission. Sadly, that was familiar as well. When one lives perpetually in the shadows, rarely being seen, much less acknowledged, or praised, censure and denigration come to be expected.

Regrettably, Meitner’s resignation is not an isolated case.

It was the same resignation that Rosalind Franklin must have felt when her boss, Maurice Wilkins, took photographs off her desk—without her knowledge or permission—and gave them to James Watson and Frances Crick, who were then credited with the discovery of the double helix structure of DNA.

It was the same resignation that the “mother of mRNA,” Dr. Kati Kariko, must have felt when her grant proposals were routinely rejected, when she was denied the promotion that would have guaranteed support for her research, when Temple University fired her, and the University of Pennsylvania demoted her. And, worst of all, when a male colleague sabotaged her search for stable employment by questioning her immigration status.

Fortunately, Dr. Kariko was finally recognized when she and her partner, Dr. Drew Weissman were honored with the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2023.

Lise Meitner hasn’t been as lucky. Justifying their actions with an antiquated rule against awarding the Prize posthumously, the Nobel committee refuses to recognize Dr. Meitner’s discovery of nuclear fission. The purpose of science is to investigate, discover, and explain the truth about the natural world; the Nobel Committee, however, seems more devoted to perpetuating sexist lies than to correcting the record.

They are perpetuating the history we have been taught: incomplete, misleading, and incorrect. This history explains a world that doesn’t exist; it’s a world in which men are at the center of human enterprise and women are at the margins supporting them as assistants, mothers, wives, and mistresses.

Knowing the work of Dr. Meitner, I went to see Oppenheimer hoping against hope that the film would illuminate, or at least nod to, history as it really is. But the story onscreen was the same—the great man of science, surrounded by teams of men in suits, vests and ties. On the outer margins were his wife and mistress, not even co-stars, bit players at best.

Isn’t it our responsibility, even our duty, as storytellers to correct the record? Whether in film, non-fiction, or fiction, isn’t it our mission to challenge the myths of history?

Let’s find Lise Meitner and all the others, the women who have been erased, and put them back into history—this time at the center of the story.

____________________________

Hannah’s War by Jan Eliasberg is available now via Back Bay Books.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·